A gift from the Nile: the sacred blue water lily

- Alessio Pimpinelli

- Nov 19, 2022

- 4 min read

Updated: Apr 19, 2023

For thousands of years the blue ‘lotus’ (more precisely, a water lily) was revered as a sacred plant in ancient Egypt. Its colours still light up the wall paintings of several tombs and its smell played an important part both in ritual ceremonies and in more mundane activities. Here it is why it was so special to the people of the Nile.

Nymphaea caerulea is a freshwater plant mainly native to eastern and central Africa. Its rhizome and seeds are edible, and ancient Nile dwellers used to grill them and consume them. However, the most notable feature of this water plant are its pale-blue flowers, which candidly emerge from the muddy marshes in which they plant their seeds.

A blue water lily in the Orman Garden at Giza. Picture by Dr Hala Barakat.

We find the flowers and their long stalks depicted on tomb walls as early as the Old Kingdom (ca. 2700-2200 BC). People are represented holding the flowers in their hands and/or up to their nose, clearly smelling their scent; in other scenes, the flowers are depicted alongside other plants and fruits in a bunch of offerings. Showing humans smelling the blue flowers demonstrate an important use that ancient Egyptians had for them: as a source of perfume. Egyptologist Dora Goldsmith (2022) has explained that the ancient people used either vegetable oil, beeswax or animal fat as the main base for their perfumes, since these ingredients produce no smell of their own. Then, the perfumers would add the chosen ingredient to the pot and cook it, so that its fragrance may scent the base. The blue water lily was a major ingredient used in such concoctions, along with myrrh, frankincense, cedar, pine and benzoin, among others.

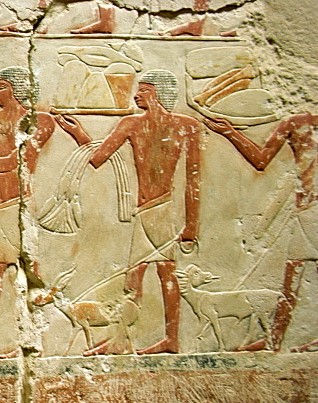

Left: image from the tomb of Ti at Saqqara (V dynasty). Notice the long stalks and flowers of the blue water lily carried by the slave. Image from robertharding.com

Right: Merit, Sennefer's wife, is holding a bunch of blue water lilies in his left hand, while others decorate her forehead. From TT96. Picture by the author.

The scenting element linked the flower with the god Nefertum, an early aspect of the creator god Atum who was later identified as the child of the Memphite couple, Ptah and Sekhmet. A passage in the Pyramid Texts (266) exhorts the deceased king to “rise like Nefertum from the lotus (i.e., lily) to the nostrils of Ra”; with this statement, the association of the flower with the sense of smell is confirmed.

Moreover, in the Book of the Dead (chapter 81a), Nefertum – in this case conceived as the early creator god himself - is said to have sprung up from the blue water lily, which had in turn originated from the watery chaos of Nun as the first aspect of creation. Such an association was probably made by observing the natural behaviour of the flowers themselves: the buds tend to open at daybreak and close at sunset, thus encouraging a link with creation myths and the idea of rebirth quite early on.

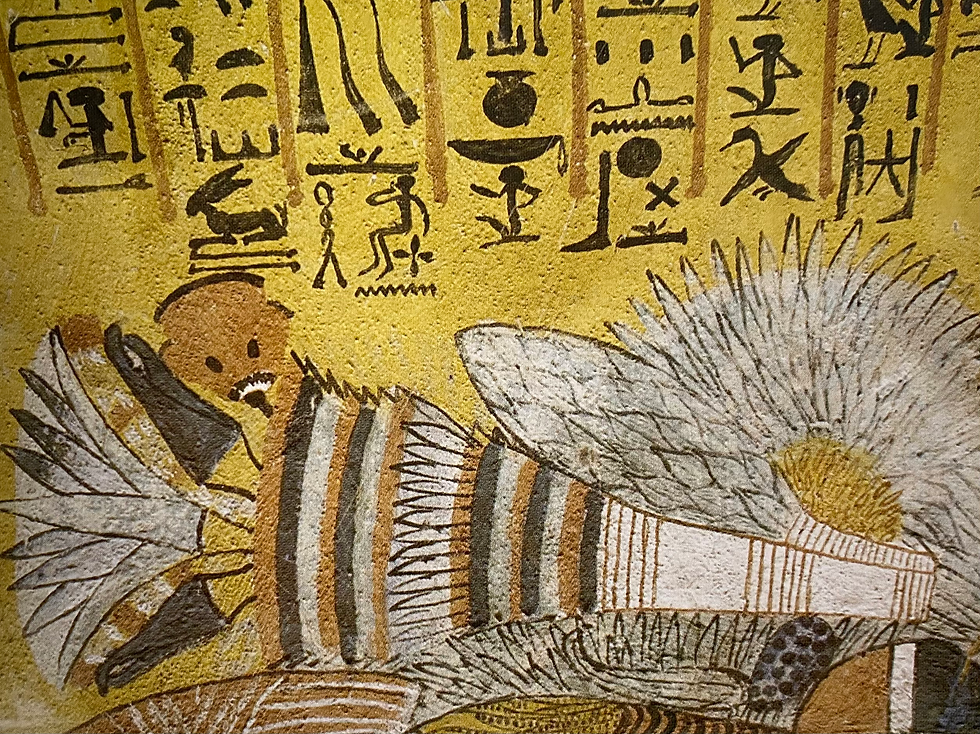

Left: Nefertum's head spring up form a blue water lily which has originated from the waters of chaos. From the papyrus of Ani, vignette 81a.

Right: A group of noblewomen is portrayed in the act of smelling water lilies and mandrake flowers. From the tomb of Nakht (TT52). Picture by the author.

The blue water lily is also shown in a stylised form on royal statuary as a symbol of Upper Egypt – that is, the Nile Valley – as opposed to the papyrus of Lower Egypt (the river Delta). The entwined plants motif, called the sema-tawy, symbolises the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt and, by consequence, the overlordship of pharaoh over the entire land.

Hapy, a personification of the Nile, in the act of entwining the blue water lily of Upper Egypt with the papyrus of Lower Egypt in the famous motif of sema-tawy. From the seated colossus of Ramses II at Luxor temple. Picture by the author.

Some years ago an interesting paper (Bertol et al. 2004) showed how the ancient Egyptians may have used the plant to treat erectile dysfunction as it naturally contains apomorphine. Such a use may be further attested by the frequent depiction of the blue lily along with poppy petals and mandrake flowers, both renown for being powerful narcotics and hallucinogenics.

Blue water lilies and poppy petals are offered in this scene from the tomb of Sennedjem (TT1). Picture by Dr Hala Barakat.

Today the blue water lily is not as widespread along the Nile as it used to be. Aside from growing in the ornamental ponds of few gardens (such as the Orman Garden in Giza or the one at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo), the plant flourishes as a weed in abandoned fields in the Nile Delta. Despite this, its evocation of ancient Egyptian practices remains as strong as ever, as attested by its continual use in perfumery and massage oils to this day.

Bibliography

Abdel Aziz, I. and Barakat, H. 2010. Guide to Plants of Ancient Egypt. Alexandria: Biblioteca Alexandrina.

Bertol, E., Fineschi, V., Karch, S., Mari, F. and Riezzo, I. 2004. "Nymphaea cults in ancient Egypt and the New World: a lesson in empirical pharmacology". J R Soc Med 97(2): 84-85.

Goldsmith, D. 2022. The Scent of Kha and Merit: A Review. Available online on academia.edu

Manniche, L. 2006 (2nd edition). An Ancient Egyptian Herbal. London: British Museum Press.

Marozzi, E., Mari, F. and Bertol, E. 1996. Le Piante Magiche: Viaggio nel fantastico mondo delle droghe vegetali. Firenze: Lettere Editore.

Wilkinson, A. 1998. The Garden in Ancient Egypt. London: Rubicon Press.

.png)

コメント