The 'birth' of diplomacy: a chronicle of international relations in the Late Bronze Near East

- Alessio Pimpinelli

- Aug 11, 2022

- 12 min read

Updated: Apr 19, 2023

Introduction

The Late Bronze Age (ca. 1550-1200 BCE) is a fascinating period: for the first time a series of regional states coexisted on the same foothold, unable to overwhelm each other militarily. Consequently, these empires developed a sophisticated diplomatic system made of letter- and gift-exchange and intermarriage alliances which, however, was not always able to thwart the occasional war outbreak. Such fluid and everchanging relationships all pursued the same goal: procuring as much political and economic advantage and prestige as possible. In this article I want to tell you about the time in which diplomacy was ‘born’: a time of war and peace, of trade and marriages, of friendships and betrayals.

This period can look extremely confusing at first and the constant change of rulers and of relations among states can sometime be hard to follow. Hence, I have adopted a ‘dramatic’ approach: the period’s main rulers are presented like actors on stage; the state they ruled over and their regnal dates are shown next to their name and each of them relates the story of his relations with his neighbours. Occasionally some rulers do interact with each other – this is based on surviving correspondence between them. I have also divided the ‘play’ into four distinct chronological acts, which hopefully will help you to find your bearings in the long list of events.

As you may expect, the cast is numerous. For the sake of clarity and order, I limited myself only to narrate the relationships established amongst the ‘big’ powers (see section below). However, it must be mentioned that a complex web of relationships also flourished between each big power and its vassal states - especially those in Syria-Palestine, which frequently switched their allegiance between Egypt and the Hittites.

At the end of the piece, you will find a short list of key readings if you fancy delving more deeply into the diplomatic world of the Late Bronze Near East. This piece is just a morsel to give you the flavour of the sophistication that intra-statal relations attained more than 3000 years ago.

Cast: the ‘big’ players (countries only)

Egypt: The land of the Nile was the strongest, largest and wealthiest state at the time. In this piece most of the actors come from Egypt as the majority of the surviving documentation comes from here.

Mitanni: This Indo-European state spanned what is today Northern Syria and Northern Iraq, with the upper course of the Euphrates roughly at its centre. Mitanni was the forefront adversary of Egypt until it was later replaced by the Hittites.

Hatti: Another Indo-European state which centred on what is today central Turkey. Hatti became Egypt’s main enemy in Syria-Palestine after overcoming Mitanni’s overlordship in the area.

Assyria: The ‘parvenu’ in the area; an intrepid, aggressive player which surprised many of its complacent neighbours.

Babylon: Babylon was a city already more than 500 hundred years old by this period. Famous for the rule of Hammurabi in the 1700s BCE, in the Late Bronze period this state had lost much of its centrality and acted more as a peripheral player in the complex system of relationships.

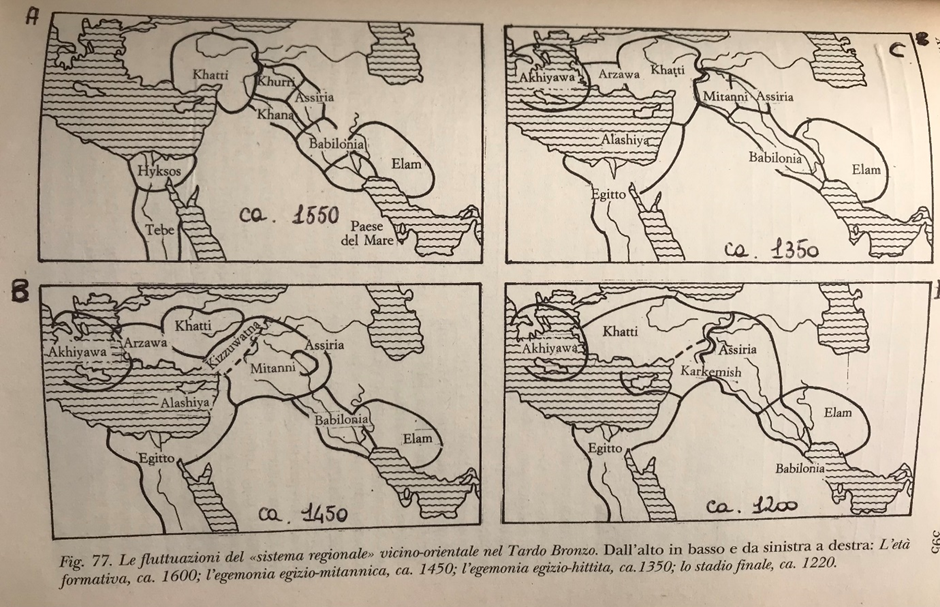

Map 1 (above) shows the geopolitical change in the Near East during the Late bronze Age.

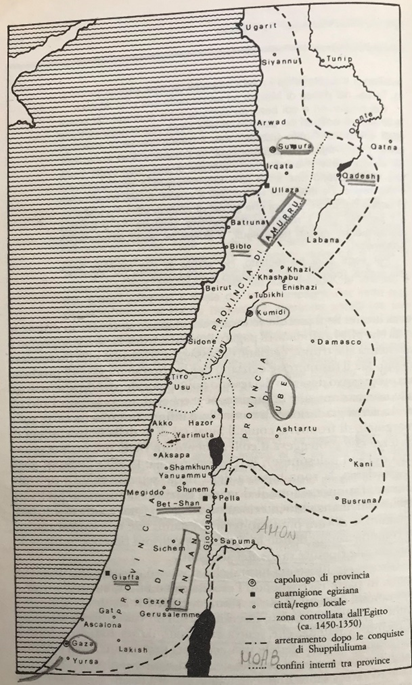

Map 2 (left) depicts the political situation in the Levant around 1400 BCE. Amurru, Ube/Upi and Canaan were the three Egyptian governorates in the area.

Both images are published in Mario Liverani's "Antico Oriente" (see 'to know more' section below)

ACT I (ca. 1450 – 1400 BCE)

Our story opens with the campaigns of the Egyptian pharaoh Thutmosis III (ca. 1479-1425 BCE). After chasing the Hyksos rulers out of his country and reuniting Egypt, the first pharaohs of the XVIII dynasty began military forays into the neighbouring areas, namely Palestine to the north-east and Nubia to the south. However, it is only with Thutmosis III that a more permanent Egyptian presence in those areas is established.

Enter THUTMOSIS III OF EGYPT (ca. 1479-1425 BCE): “When I came to the throne I was only a child. For a while, my step-mother Hatshepsut ruled as pharaoh alongside me, until she passed away and I was able to take the reins of government fully in my own hands. Throughout the rest of my reign I conducted 17 campaigns in the areas which today are known as Palestine and Lebanon. Among my military exploits you may have heard of the siege of the city of Megiddo (that is where your word ‘Armageddon’ comes from, I was told). Once I even entered the territory of my neighbour Mitanni and crossed the Euphrates (I had a stela engraved just beyond the river to mark my achievement); however, I could not realistically hold my power onto such a faraway and organised state, so Shaushtatar of Mitanni and I decided to settle the border along the Oronte river. All the areas south of it, including the prosperous kingdom of Amurru, the wealthy town of Ugarit and the land of Canaan, became my vassals and I established governors there to collect tributes and to look after my affairs.”

Enter SHAUSHTATAR OF MITANNI (contemporary of Thutmosis III): “After I established my border with Egypt, I was free to pursue my goals elsewhere. I turned my attention to Assyria in the east, beyond the Euphrates (at the time still quite a weak state, politically speaking). I crossed the river and invaded the land; I conquered and looted Assur, the capital, and brought back with me golden and silver gates which I established in my own capital city. With me, Mitanni reached the peak of its power and expansion”.

Exit Thutmosis III

Enter AMENHOTEP II OF EGYPT (ca. 1425-1401 BCE): “That Mitanni was at its zenith I could see it with my own eyes. Twice I had to bring my armies into Palestine and Lebanon as the Mitannians encouraged my vassals to rebel. I was eventually victorious (I cannot clearly remember how right now) and, finally, Mitanni and I decided to put our differences aside and come together in peace. Oh, and did you know? I was so successful that even Kara-indash, the ruler of distant Babylon, sent me gifts to congratulate me! It was the first time that something like that happened!”

All exit

ACT II (ca. 1400-1330 BCE)

The second phase sees the establishment of peace and intermarriage alliances between Egypt and Mitanni, the latter being increasingly threatened by the rising powers of Hatti in the north and, later, of Assyria in the east. This period is also documented by the incredible “Amarna Letters” – an archive of diplomatic correspondence between the Egyptian pharaohs and their neighbouring states and vassals.

Enter ARTATAMA I OF MITANNI (contemporary of Amenhotep II and Thutmosis IV of Egypt): “I finally made peace with Egypt and tried to establish deeper relationships with them. Amenhotep II was quite suspicious, however, and nothing came of it. Then his son Thutmosis IV came to the throne and he asked the hand of a daughter of mine in marriage; I refused (I can’t really remember why I had changed my mind). But Thutmosis IV was so persistent that he asked me seven times for it! Eventually, I relented; in fact, now I am quite glad I did so, as the alliance brought a period of peace and border security between our two great states!”

Exit Artatama I of Mitanni

Enter AMENHOTEP III OF EGYPT (ca. 1390-1353 BCE): “After I became pharaoh, I continued my father Thutmosis’s policy towards Mitanni. The Mitannian king Shuttarna offered me in marriage the hand of his sister Kiluhepa; we got married in my 10th regnal year. She arrived with a retinue of 317 women – not one less! It was truly a marvel; I was so impressed that I even had a series of scarabs inscribed with the description of her arrival in Egypt!”

Enter KADASHMAN-ENLIL I OF BABYLON (ca. 1374-1360 BCE): “Esteemed brother, Pharaoh of Egypt, I know how fond you are of foreign brides. I do wonder how my sister, the daughter of my predecessor Kurigalzu, is faring at your court; since you married her, I have not heard a word from her, so much that I believe she is dead! Please prove me wrong. Otherwise, how can I confidently send you a daughter of mine as a bride as well? Or perhaps you could send a daughter of yours here to Babylon to become my bride, for once!”

AMENHOTEP III OF EGYPT: “Egregious brother, ruler of Babylon, your sister is alive and well. We are about to celebrate a great festival here and we are all looking forward to having some fun and getting drunk. Anyway, I am afraid I am not able to fulfil your request: since the dawn of time no daughter of the king of Egypt has ever been given in marriage to anyone. What if I send you such a quantity of gold so that you can finally complete that building project of yours? Oh, and I shall also include furniture of the finest quality for your enjoyment!”

KADASHMAN-ENLIL I OF BABYLON: “Dear brother, although I am quite annoyed that you did not invite me at your festival, I confess that what you proposed sounds like an excellent idea! I am looking forward to your gifts and gold; you shall have your Babylonian bride soon”.

Exit Kadashman-Enlil I of Babylon

Enter TUSHRATTA I OF MITANNI (contemporary of Amenhotep III and Akhenaten): “Dear brother Amenhotep, we have not had a great time here in Mitanni recently. You may have heard of one Shuppiluliuma, king of Hatti, who has ravaged my country more than once. It all happened quite suddenly, really; at first, I was able to repel him beyond my borders, but then he unexpectedly came back stronger than before. I heard he was even able to reach your domain of Amurru after sweeping over my poor land. He is definitely a foe we need to be mindful of. Shall we arrange another marriage? I shall send my sister Taduhepa to you as soon as possible”.

AMENHOTEP III OF EGYPT: “That shall do, brother. Although I am a little old, I shall gladly accept your sister as a bride. And don’t worry; in case I die, my son Amenhotep (later Akhenaten) will take the harem over and shall become her new husband”.

Exit Amenhotep III of Egypt

Enter SHUPPILULIUMA I OF HATTI (ca. 1360-1330 BCE): “I am called the founder of the new Hittite empire. As a fierce warrior, I expanded the land of my forefathers in every direction: I overcame Mitanni (who are still around, but much weakened) and snatched Ugarit, Qadesh and Amurru from Egyptian hands. It was quite easy, really; Egypt has recently been in turmoil. I am not really sure why they did not respond promptly to my attacks on their vassals but I have heard that their ruler, one Akhenaten, has decided to cut ties with their old gods and has even built a new capital city out of the sands. Anyway, the Oronte river is now the border between our two countries. I also married a daughter of the Babylonian king, thus making sure that Babylon supports me instead of Mitanni”.

Enter ASHUR-UBALLIT I OF ASSYRIA (ca. 1360-1328 BCE): “Thanks to your action against Mitanni, brother Shuppiluliuma, I was able to lead Assyria to strength and power unknown to my forefathers (although I did not like the fact that you placed a filo-hittite ruler on the throne of Mitanni). I took the name of ‘great king’ and even sent a delegation to Akhenaten of Egypt. I heard that Burna-Buriash of Babylon complained to the pharaoh about this, claiming I am his vassal; as if! Indeed, Burna’s son has even taken my daughter as his bride! And when Babylon revolted, I succeeded in placing my great-grandson on its throne!”

Exit all

ACT III (ca. 1330-1250 BCE)

The third act portrays the great struggle between Egypt and Hatti for the control of the areas around the Oronte river and the subsequent peace established between them – a peace which will endure until the end of the Bronze Age. This phase also marks the sudden and unexpected rise of Assyria to the ranks of great power.

Enter MURSHILI II OF HATTI (ca. 1330-1295 BCE): “My father Shuppiluliuma did not leave me with a pacified realm. At his death, all the people he had subdued revolted against me, whilst plague ravaged my land. Eventually, I could re-establish order and I even annexed the powerful state of Arzawa to my kingdom. The Egyptian pharaoh Horemheb tried to reconquer the province of Amurru, but to no avail.”

Exit Murshili II

Enter SETHY I OF EGYPT (ca. 1290-1279 BCE): “And then it was my turn to try and recapture our Syrian territories. My main objective was to recapture from Hatti the powerful city of Qadesh on the Oronte river; in this I was victorious, although my success was not to last, as you shall see.”

Exit Sethy I of Egypt

Enter RAMESSES II OF EGYPT (ca. 1279-1212 BCE): “Indeed Qadesh was soon after retaken by the Hatti ruler Muwatalli. I could not let this affront go unpunished! Hence, I led a military expedition during my fifth regnal year to recapture the city. I obviously boasted about my glorious deeds when I came back home - I basically littered the whole of Egypt (and beyond) with depictions of my exploits; however, in all fairness, I must admit that things in the area did not change that much. Qadesh and Amurru remained in Hittite hands, although I like to think that I was able to maintain Egypt’s honour high. But now, look, Muwatalli of Hatti has died; a civil war ravages the country; who shall win?”

Enter HATTUSILI III OF HATTI (ca. 1267-1237 BCE): “Brother, I am Hattusili, Muwatalli’s brother and legitimate heir of Hatti. My nephew was unfit for the throne and I thus ousted him. Now that my rule is secure (and I do need new friends) I do wonder, would you like to make peace? Our countries have been at war for so long that I cannot even recollect how it all started!”

RAMESSES II OF EGYPT: “Indeed why not, brother? I propose that we mutually help each other if we are attacked by a third party or if one of our vassal-states rebels; I will also guarantee your son’s succession to the throne of Hatti, if I outlive you; and what about not sheltering each other’s country’s fugitives?”

HATTUSILI III OF HATTI: “It sounds perfect to me, brother. Shall we cement all this with a marriage? I am willing to send one of my daughters to you as bride.”

RAMESSES II OF EGYPT: “That shall do – I shall call her Maat-hor-Neferoura and I will make her one of my Great Royal Wives!”

Enter ADAD-NIRARI I OF ASSYRIA (ca. 1295-1263 BCE): “Brothers, you should now be welcoming me, the ‘king of the universe’! Thanks to the war you waged against your nephew, Hattusili, I was able to take for myself what was left of Mitanni from your sphere of influence. Now that we share a border, shouldn’t we establish a formal brotherhood?”

HATTUSILI III OF HATTI: “I reluctantly admit that you now rank in the number of great kings, Adad-Nirari, but there is no way that we can possibly be brothers. Do we perhaps share the same father, the same mother? Moreover, it is custom that when a great king is acclaimed, the others send him gifts. Have you perhaps done so? You definitely do not resemble my brother Kadashman-Enlil II, king of Babylon, with whom I am in very good terms these days. I have heard you have a good relationship yourself with him, don’t you Ramses?”

RAMESSES II OF EGYPT: “Indeed I do, brother. I have taken one Babylonian princess in marriage to cement Egypt’s partnership with Babylon. May our friendship endure!”

All exit.

ACT IV (ca. 1250-1180 BCE)

The final act deals with the aggressive exploits of Tukulti-Ninurta of Assyria and concludes with the collapse of the interregional system following the arrival of new people in the region.

Enter TUKULTI-NINURTA I OF ASSYRIA (ca. 1243-1207): “After the events narrated above, my father Salmanassar I decided to annex Mitanni to our empire. This did not go down too well with the Hittites, though. Since then, our two states have been at war. However, the river Euphrates is too big an obstacle for any of us to control what is beyond it, and thus it remains our border to this day. What I put my efforts on, however, was Babylon. The then-king, Kashtiliash IV, thought well to exploit my accession to the throne and my youth to try and recapture some of its northern lands. What a mistake he made! Not only did I defeat him in battle; I also captured him, took him to Assur – my capital city – and then rushed to Babylon itself, which I occupied and of which I became king. Alas, it did not last long; as I was infamously killed in a palace plot, Babylon was abandoned and its former rulers restored. Yet my exploits shall never be forgotten!”

Exit Tukulti-Ninurta I of Assyria

Enter RAMESSES III OF EGYPT (ca. 1186-1155 BCE): “It falls to me, the last great pharaoh of the New Kingdom, to recount how our world ended. It was caused by a combination of factors, as it usually is in such situations: long-term demographic crisis; recurrent famines and plagues; an ever-increasing gap between the elites and the rest of the populace; and, finally, the arrival of new people. We called them ‘Sea-People’ as they swept down from the Mediterranean Sea - but I am not sure from where they actually were from; I only know that they were made up of several tribes. Some of them had already appeared during the reign of my predecessor Merenptah (ca. 1213-1203 BCE), who defeated them in battle; but nothing could really prepare us for what was awaiting us. They started with Hatti: they encroached it from the west and washed away their great empire, which never saw the light again. Then, they rushed down the Levantine coast, chasing away my troops and destroying the local city-states, including Ugarit. Finally, they reached the Egyptian delta; I was able to fight them off repeatedly and keep them at bay, but Egypt lost control of its Levantine vassals. All international relations were severed; I later got to know that Assyria was severely weakened, although it was able to retain its core territory. Babylon, on the other hand, was conquered by eastern enemies, its ruling dynasty extinguished. A new political order came into being; nothing would ever be the same again”.

Exit Ramses III of Egypt

To know more:

· Bryce, Trevor, 2014. Letters of the Great Kings of the Ancient Near East: The Royal Correspondence of the Late Bronze Age. Abingdon: Routledge.

· Cohen, Raymond and Westbrook, Raymond, 2000. Amarna Diplomacy. The Beginnings of International Relations. Baltimore and London: The John Hopkins University Press.

· Liverani, Mario, 2014. The Ancient Near East: History, society, economy. (original Italian edition published by Editori Laterza). Abingdon: Routledge.

· Redford, Donald 1992. Egypt, Canaan and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

.png)

Comments