Amenhotep II: 5 reasons for why you should know who he was

- Alessio Pimpinelli

- Aug 28, 2022

- 9 min read

Updated: Apr 19, 2023

Squeezed between some of the biggest names of ancient Egypt (Hatshepsut, Thutmosis III, Amenhotep III, Akhenaten) lies a less-known pharaoh who, nonetheless, marked a relevant juncture in the political and artistic development of Egypt’s 18th dynasty. In this article I want to bring back to you the story of Aakheperura (‘Great are the manifestations of Ra’) Amenhotep and show you five reasons for which his rule stood out in the history of Egypt’s most famous dynasty.

1. Friend Power

Amenhotep II inherited the Egyptian throne at his father Thutmosis III’s death in around 1426 BCE. Scholar Susan Redford noticed, however, that Amenhotep had not been Thutmosis’s intended heir – not initially at least. It seems than an elder prince, one Amenemhet (son of Thutmosis III’s first Great Wife Satiah) had had such a privilege. However, Amenemhet had predeceased his father, and the pharaoh was forced to find another wife once Amenemhet’s mother also passed away. This new Great Wife, Merytra, provided Thutmosis with plenty of offspring, including his next heir Amenhotep.

Amenhotep was soon sent to Memphis, the historic capital of Egypt, where he was brought up in the company of other nobles’ sons, who are identified by the peculiar title “children of the nursery”. Although this title was not new, what is remarkable is the attested close relationship between Amenhotep and his friends even after he had become pharaoh: many of these individuals were appointed by the new king to key places in the Egyptian administration. Maanakhtef became “chief steward of the king”, one of the closest positions to the pharaoh. Usersatet was Amenhotep’s “overseer of the Southern Lands” – i.e., Nubia, a vital region where Egypt’s gold resources were acquired. Userhat was in charge of counting the country’s “rations”, while Paheqamen oversaw all the pharaoh’s construction works. Just by looking at some of these titles one can appreciate the paramount nature of such positions: from his own affairs to foreign ones, from food provisioning to building projects, Amenhotep made sure that he had a firm grip on the whole administration of the state.

Was Amenhotep simply favouring friends from his youth or was there anything more underlining such choices? Was he trying to secure his rule by allocating key places in the administration to people whose loyalty he could be sure of? It is intriguing to consider the latter option, especially as Amenhotep had not been his father’s primary heir. Whatever the key reason, the close bond between the pharaoh and his youth circle, attested by their number and careers, is what really stands out.

2. Pharaoh’s women – or not?

Pharaohs did not always have extensive harems on the likes of Ramesses II’s. However, rulers tended to highlight the presence of at least one major wife when commissioning their decorative projects – usually the highest one in rank, the king’s “Great Wife”. For Amenhotep II this was not entirely the case.

We know that Amenhotep had at least one wife, Tia, who is better known thanks to the place she held during her son’s reign, Amenhotep’s successor Thutmosis IV. However, Tia was not Amenhotep’s main spouse. As the existence of many princes is attested, Amenhotep must have had more than one wife. What is unusual, however, is that none of them was publicly acknowledged as the pharaoh’s “Great Wife”. That honour went to Merytra, Amenhotep’s mother. Academic Betsy Bryan has suggested that this unusual situation reflected Amenhotep’s conscious “rejections of the dynastic role played by princesses and queens”. Considering that Hatshepsut’s memory was still fresh at this time (Amenhotep was indeed responsible for continuing the erasure of the female pharaoh’s name already begun by his father Thutmosis III), it may not be so unusual that the pharaoh had decided to restrain the visibility of his women and their positions, so to avoid anything similar repeating itself.

Amenhotep II and his mother Merytra in a relief from Karnak temple. Drawing from Richard Lepsius’s Abt III, bl. 62.

3. A first-rate sportsman

Possibly the most characteristic feature of Amenhotep’s reign are the ways by which the pharaoh repeatedly stressed his physical prowess and his suitability to rule. The portrayal of pharaohs in the act of performing some athletic activities was nothing new in Egyptian art, but the importance which Amenhotep assigned to such performances was not to be seen again.

Scholar Peter der Manuelian noticed that the depiction of the king as an oarsman in an exclusive athletic context is a theme which appears for the first time during this reign. Moreover, Amenhotep appears to have been particularly fond of horses, a trait also witnessed by his personal cult to Astarte, a Syrian deity linked to horses, chariotry and warfare.

This fragment shows Amenhotep (identified by the name in the cartouche, Aakheperura) feeding one of his horses. The drawing is after Hall, Catalogue of Scarabs 161, no. 1640. The piece is currently at the British Museum (no. 4074).

However, it seems that Amenhotep’s favourite activity was archery. “There was not one who could draw his bow”, boasts the Great Sphinx Stela in Giza. The king prided himself of a feat in particular: the shooting of target coppers by the simple means of bows and arrows. Some scholars have argued that this could not have been materially possible; on the other hand, Javier Gimenez has highlighted the ritualistic functions that such a scene may have encapsulated. Although it was not the first time that this was represented, what is striking is Amenhotep’s unusual stress of his skills in the material record: no pharaoh either before or after him reproduced this scene as many times as he did. He was so fond of archery that he once even challenged his retinue to a competition, which is a unique reference in the whole pharaonic history, as recorded in an inscription from Medamud (a town north of ancient Thebes).

All these feats have conveyed to us the image of a very athletic and sportive ruler – a pharaoh whose accomplishments would be indeed hard to surpass.

In this relief Amenhotep is shown on his chariot whilst shooting at a copper target. His feats were legendary, according to his Great Sphinx Stela: “it was a deed which had never been done before, nor heard of by report”. The relief is currently at the Luxor Museum (no. J. 129).

4. Peacemaker

“(He is) one who rages like a panther when he treads the battlefield” (Amada stela)

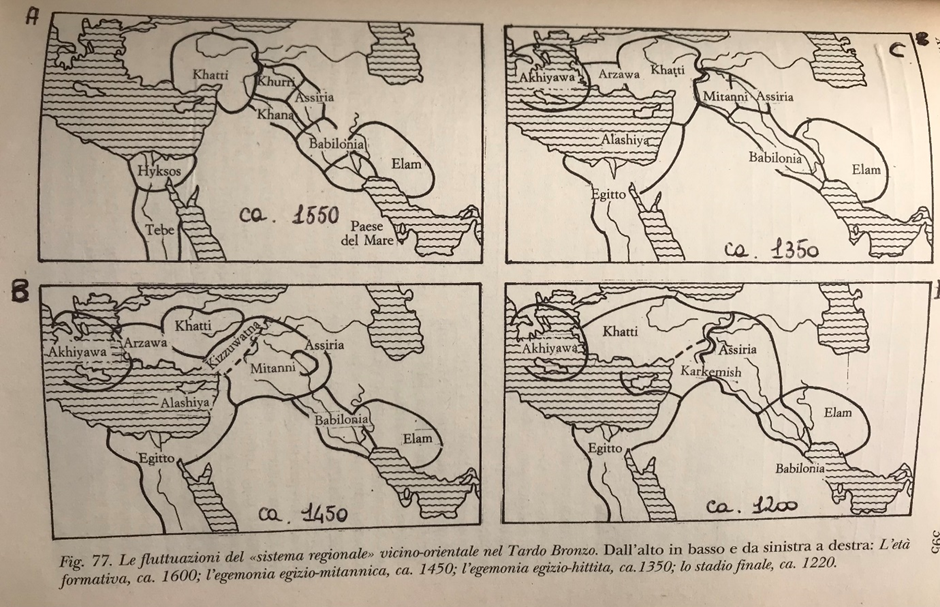

After Thutmosis III’s extensive wars in the Levant, Egypt had come to share a border with Mitanni, a powerful regional state centred on the upper course of the river Euphrates. During his twenty-six-year reign, Amenhotep led three military campaigns in the region that we are aware of.

The first campaign, waged in the pharaoh’s third year, is vaguely recorded; the king appears to have led an expedition up to an area named ‘Takshy’ (near the old town of Kadesh), where seven enemy chiefs were taken captive and were brought back to Egypt in chains. The Amada stela records that Amenhotep had six of these leaders hanged off the walls of Thebes, whereas one was carried up the Nile to modern-day Sudan and displayed off the walls of the main centre in the area, Napata. The message could not be clearer: whoever rebelled against pharaoh would experience pharaoh’s wrath. As Takshy was an area already under Egyptian influence, it is probable that Amenhotep had to travel there to quell a rebellion.

The second campaign possibly began because of a direct Mitannian interference in the affairs of Egyptian vassal states. In year 7 Amenhotep set out from Egypt and reached modern day Galilee, where he recaptured an unidentified town called Shamash-Edom (see map below). He then crossed the Oronte river near the city of Qatna, where he engaged his enemies in battle – all alone, according to the Karnak stela (this was a typical propagandistic tool which is also known from Ramses II’s narration of the battle of Kadesh). Allegedly, Amenhotep captured local princes and warriors and he then pierced two hammered-copper targets with his bow (see above). Heading back south, in an area called Sharon, a Mitannian envoy carrying an inscribed clay tablet around his neck was captured by the pharaoh’s army. This has been interpreted by some scholars as the proof of the Mitanni’s meddling in the Levant after Thutmosis III’s settlement of the area.

This drawing shows Amenhotep’s itinerary during his year 7 campaign in the Levant. Image after Peter Der Manuelian, 1987.

Not long passed, however, that another rebellion in Canaan broke out. Was this due to Mitannian action as well? We do not know. In his ninth regnal year, Amenhotep was forced to leave Egypt again. This time the area of operations was much narrower in scale (see map below). According to the Memphis stela, Amenhotep reached Canaan along the ‘Via Maris’ (a road which followed the coast from the eastern Delta up through Gaza) and, during the journey, he had a dream in which the main Theban god Amun pledged his support and protection to the pharaoh. After capturing the town of Anaharath (modern Tell-al-Ajjul), a prince named Qaqa was brought to Amenhotep for punishment: had he been one (or the only one) of the instigators of the rebellion? Unfortunately, we do not know.

This drawing shows Amenhotep’s itinerary during his year 9 campaign in the Levant. The highlighted place is Anaharath, the town mentioned in Amenhotep’s narration of this expedition. Image after Peter Der Manuelian, 1987.

What we do know, though, is the way Amenhotep decided to end the recount of his military exploits: “When the chief of Naharin (Mitanni), the chief of Hatti and the chief of Samaar (Babylon) heard of the great victory which I had made, each one […] presented (me with) all kinds of offering of all foreign lands”. This final statement in the Memphis stela, combined with the absence of further wars in the textual record, leads us to believe that relationships with Mitanni changed after the year 9 campaign and that they remained so for the rest of Amenhotep’s reign. However, some scholars pointed out that no marriages between Mitanni and Egypt are known for this period – marriage alliances being both a concrete proof and a reminder of an existing peace between two states. Only for Thutmosis IV, Amenhotep’s son, the first marriage between a pharaoh and a Mitannian princess is recorded. Even though Amenhotep may not be credited for sure with the establishment of a formal peace between Egypt and Mitanni, his activity in the Levant and his dealings with his foe should not be overlooked; his actions created the basis for that same peace which later endured from the time of his successor until the fall of Mitanni itself.

5. ‘Deadly’ innovations

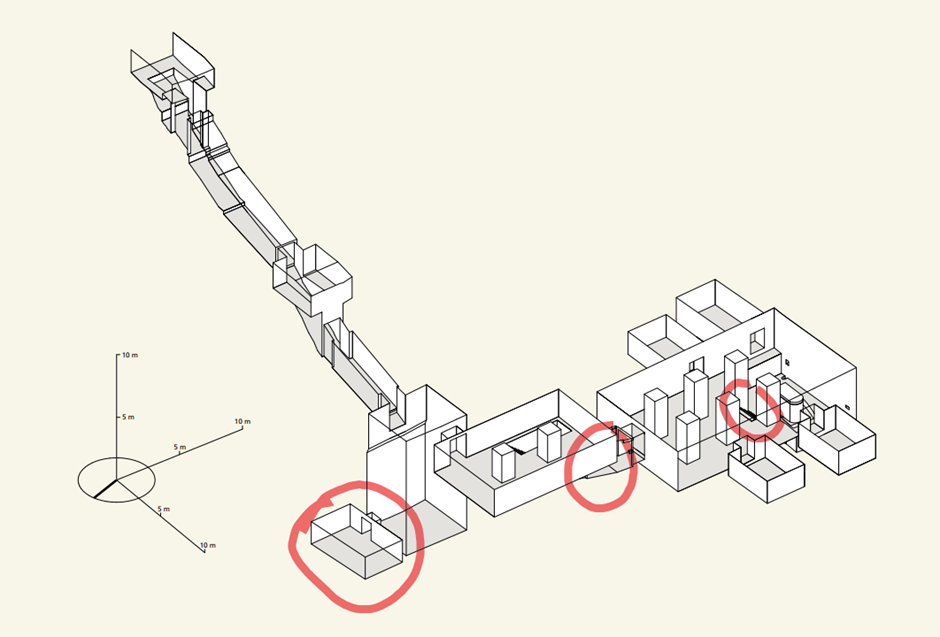

At his death in around 1400 BCE, Amenhotep was ready to join his father and his immediate predecessors in the new royal necropolis in western Thebes, today known to us as the Valley of the Kings. The planning, digging and decoration of the tomb took place during the king’s lifetime, although we are not sure to what degree the pharaoh influenced the stylistic choices of his tomb. In spite of this, Amenhotep’s tomb (today numbered KV35) shows some features which would later be adopted by many of his successors for generations to come.

KV35 presents a symmetrical shape for the first time, with straight angles and regular-shaped rooms. A chamber was added at the bottom of the well shaft, an element also adopted in the burials of Amenhotep’s successors Thutmosis IV and Amenhotep III. A corridor was inserted to separate the antechamber and the burial chamber. The latter was also divided into two parts: an upper section with six pillars and a lower section (the ‘crypt’) where the sarcophagus still lies.

Plan of KV35 from the Theban Mapping Project. I have encircled in red the new features of the tomb: the room at the bottom of the well-shaft; the corridor now linking the antechamber and the burial chamber; and the division of the latter into two parts by the means of some steps.

In terms of decoration, the walls of the burial chamber display the sun’s night journey in the Duat as in the tomb of Amenhotep’s father, Thutmosis III. For the first time, though, the pillars of the burial chamber depict fully drawn figures of the pharaoh whilst standing or making offerings in front of various deities. This element will remain in vogue until the very end of the New Kingdom, some 400 years later.

Amenhotep II standing in front of the mummified Osiris, king of the Underworld. Image from the Theban Mapping Project.

Fun fact: Amenhotep’s mummy was the only other royal mummy who was found still lying in his sarcophagus at the time of his tomb’s discovery in 1898 (the other one being Tutankhamun). The mummy is the one of a man around 40 years old, taller than most of the other royal corpses (around 1.67 m) and with wavy brown hair spotted with grey around the temples.

To know more:

Aharoni, Yohanan 1960. “Some geographical remarks concerning the campaigns of Amenhotep II”. In Journal of near Eastern Studies, 19:3, pp. 177-183.

Bryan, Betsy 2000. “The Eighteenth Dynasty before the Amarna Period”. In Ian Shaw (ed.) The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 207-264.

Der Manuelian, Peter 1987. Studies in the Reign of Amenophis II. Hildesheim: Gerstenberg Verlag.

Gimenez, Javier 2017. “Integration of foreigners in Egypt: the relief of Amenhotep II shooting arrows at copper ingots and related scenes”. In Journal of Egyptian History 10, pp. 109-123.

Redford, Donald 1965. “The Coregency of Thutmosis III and Amenophis II”. In Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 51, pp. 107-122.

Reeves, Nicholas and Wilkinson, Richard 1996. The Complete valley of the Kings. London: Thames & Hudson.

Van Siclen, Charles 1982. Two Theban monuments from the reign of Amenhotep II. San Antonio: Van Siclen Books.

.png)

Comments