Domitian: greedy tyrant or skilful administrator?

- Alessio Pimpinelli

- Jan 25, 2023

- 7 min read

Updated: Apr 19, 2023

In 96 AD Domitian, the last emperor of the Flavian dynasty, was killed in a palace coup through the help of some servants. Immediately after his death, the Senate of Rome declared the emperor’s damnatio memoriae – that is, the cancellation of Domitian’s every image and deed in the records: his name was erased from inscriptions; many of his statues were reshaped or destroyed; and some of his edicts were revoked. To what was such a hostility due? To what extent does this emperor’s negative image - as seen through the extant sources - correspond to truth?

The Sources

The scant surviving historical sources which deal with Domitian’s reign (Suetonius’s Life of Domitian; Cassius Dio’s Roman History; and Tacitus’s Agricola) all portray the emperor in a negative light, both in his character and in his rule. The princeps is shown as violent, vicious and envious, a calculating man always ready to exact revenge and to pursue his own interests cunningly. To such deprecations are opposed the views of those authors (Martial, Silius Italicus, Statius) who were literary active during Domitian’s reign. In their works these poets tend to eulogise the emperor’s personality and achievements. How can we thus reconcile such opposing views?

We should see such a contrast as the proof that each author had a personal agenda in mind when writing his work; by consequence, their remarks on Domitian can be potentially flawed or exaggerated. Martial and Statius, for instance, praised the princeps in their poems in order to receive economic benefits which could ameliorate their poor background. Tacitus, on the contrary, belonged to the senatorial order, the class which had suffered the most (politically and economically) under Domitian’s reign; this greatly explains his frequent vicious attacks on the sovereign.

Statue of Domitian in military apparel at the Vatican Museums, Rome. Picture by the author.

Governing the Senate

Domitian had never hidden his preference for an autocratic style of government, in which the epicentre of power was visibly moved from the Senate into the hands of the ruling emperor. This contrasted with the policy inaugurated by Augustus a century earlier, in which the princeps had to (in appearance, at least) take heed of the counsel of the Senate before taking any important decision. Domitian assigned relevant administrative posts to either equestres (lit. “knights”) or liberti (freed slaves) of his own household, who responded directly to him and who, in so doing, further reduced the senators’ actual power and influence. The emperor pursued this policy in the belief that trust and loyalty were far more important components of an administrator’s character, rather than an illustrious birth and high rank; all this naturally led to the rise of the senators’ hostility towards him.

But the seeming reason for which Domitian may have passed down in history as a bloodthirsty tyrant is the execution of many senators under his watch. The aristocratic sources which relate these events see the cause of this in Domitian’s jealousy and greed. According to these records, in disposing of so many noblemen, the emperor was able to come into possession of their enormous wealth and to use it to finance his luxurious lifestyle.

If we analyse the tally, however, Domitian had ‘only’ eleven senators (out of 300 in total) killed during his fifteen-years reign – too few to justify all the expenses that he would have incurred meanwhile (it should be said that some others were exiled, however). The main reason behind such acts was justice: all the members who had been either executed or sent into exile had been mainly corrupted or had embezzled funds to the detriment of the state. This does not imply that personal jealousies and dislike were not part of the picture; however, they were not its main feature.

Despite the true reasons, it was such executions which had Tacitus exclaim that “freedom is now back, enough with this tyrant!” (Life of Agricola, chapters 1-3) once the princeps had been assassinated. It is evident from the sources that Domitian’s stance towards the senators hardened towards the end of his reign; the majority of the executions took place in the 90s AD, especially after the averted rebellion of the general Saturninus on the Rhine in 89 AD. Contemporary historians such as Brian Jones and Pat Southern see the reason of this in the progressive ‘gloominess’ of Domitian’s character in his last years, during which the emperor’s natural diffidence worsened to the point of becoming paranoia. Therefore, a combination of personal motivations, the exaction of justice and excessive fear of disloyalty may have been at the base of the senatorial executions and exiles.

A military man

Based on the above, we can easily see from where such a negative vision of Domitian’s rule may have stemmed; and this tradition was later bequeathed to posterity by authors of senatorial rank (since the earliest times, only senators used to write about history).

Tacitus, amongst others, also had personal reasons for discrediting the emperor. Around 85 AD Domitian summoned back to Rome from Caledonia (modern-day Scotland) Tacitus’s father-in-law, the general Agricola, who had been campaigning there against local tribes; the summoning, according to Tacitus, prevented Agricola from completing the military occupation of the land and from pursuing further military glory. Tacitus accused the emperor of jealousy and, in addition, of being the mastermind behind Agricola’s sudden death after his return to Rome. However, Domitian probably had more practical reasons for Agricola’s recalling from the battlefield.

Whilst the general was busy campaigning in Caledonia, a new threat had started to emerge on the Danube: the Dacians, a populace centred in modern-day Romania and led by a newly established and highly martial king, Decebalus. Domitian thus needed to redistribute his human and military resources accordingly and the subduing of Caledonia (a poor and faraway region with very little economic and strategic interest) lost its importance in the emperor’s eyes.

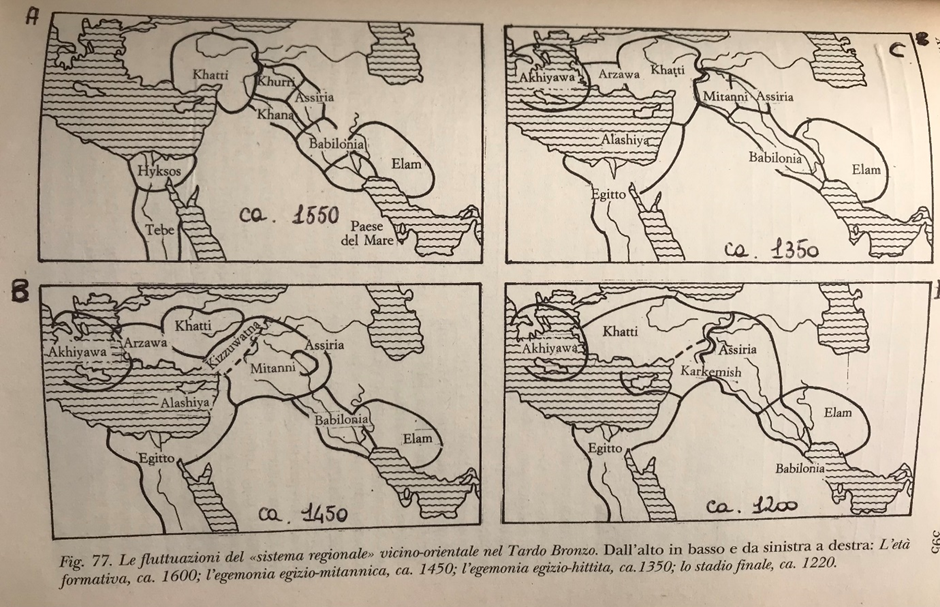

The limes in Upper Germania is probably the most famous of the fortified Roman frontiers. The extensive works of Domitian are highlighted in light blue. It was the first time that an organic series of encampments, roads and outposts was created. Image from Wikipedia.

The fact that Domitian was a popular military man is shown by the reaction that both ordinary legionnaires and the praetorians had at the news of his death. According to Suetonius (Life of Domitian, 23), the soldiers were deeply aggrieved at his murder and they “would have exacted revenge, had it not been for the lack of a leader among them”. The emperor was the first who, since the time of Augustus, had spent much of his time at the frontiers, developing a close bond with his military personnel and his armies. Domitian personally led both the expedition against the Germanic tribe of the Chatti in the year 82/83 AD and the successive defensive wars on the Danube against the Dacians and the Sarmatians. This “visibility” was accompanied by a policy of benefits for the soldiers, including an increase of their pay; such expenses were only possible thanks to a strong economy and to the effective administration characterising the reign.

Governing the State

Domitian got personally involved with every aspect of government. Throughout his reign he kept in check the value of the currency so that it did not devaluate. He fought corruption, and a new position, the curator, was established to investigate the abuse of public funds in several towns. Even Suetonius (Life of Domitian, 2) acknowledges that “during his reign, bureaucrats in Rome and in the provinces were more honest and restrained that they had ever been”.

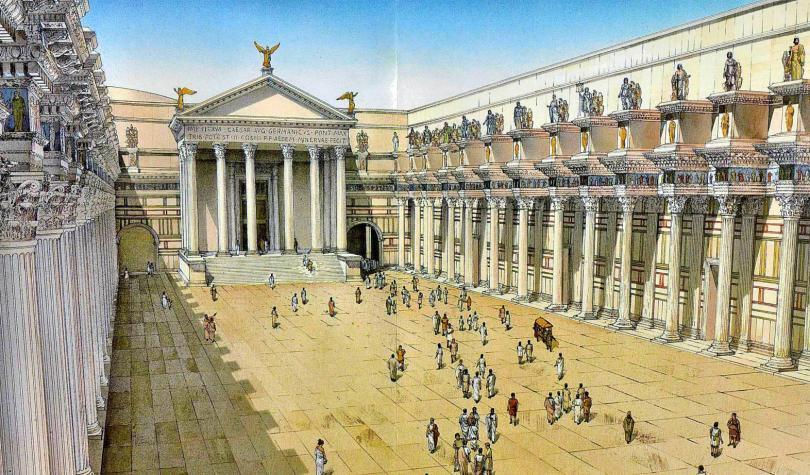

The funds acquired through such policies were used not only for military gains, but also for the realisation of an extensive and lavish building programme. In Rome only, more than fifty buildings were either erected, refurbished or completed during his fifteen-years reign. Some famous example among these includes: the Forum Transitorium (or Forum of Nerva); the Arch of Titus in the Roman Forum; the Stadium (modern-day Piazza Navona); the large palatial complex on the Palatine; and the beginning of the excavations for a new forum, which later became the Forum of Trajan. Moreover, Domitian ordered the erection of the limes (lit. "border"), an organised and interconnected series of fortresses, encampments, outposts and roads with the aim of better defending the frontiers and of easing the movement of troops. The most famous example of such a system was on the Rhine, built to contain the ever-shifting Germanic tribes beyond.

In such troublesome areas, however, Domitian also resorted to diplomacy when possible: he tried putting tribes against each other or strived to create ‘buffer states’ loyal to Rome between enemy territories and the imperial frontiers. Notwithstanding these great expenses, at his death the imperial coffers were full.

A possible reconstruction of the Forum Transitorium, ideated and built by Domitian but inaugurated by his successor Nerva. The temple at the far end was dedicated to Minerva, patron goddess of the emperor. Image from the website https://colosseumrometickets.com

Conclusion

Domitian has been accused of being a greedy tyrant whose sole goal was murdering senators out of sheer jealousy in order to acquire vast patrimonies to spend in an idle and opulent life. By carefully perusing both literary and archaeological material, however, a different image of the emperor emerges: an effective administrator, whose attention to detail and carefully planned policies led the empire to economic prosperity and to enhanced border security.

Domitian has been generally portrayed in a negative light (and, probably, his being introverted and ‘gloomy’ played a major part in that), but it is fair to remember that it was thanks to his attentive economic policy that Trajan’s wars in Dacia were funded; that it is thanks to him that Rome was embellished with monuments that still ornate it to this day; and that the idea of limes as we understand it was conceived under his watch.

We will never know the truth behind 'Domitian the person'; but it is fair to state that there are also a lot more positives to be said about 'Domitian the emperor' than the Roman senators would have us believe.

References

Bianchi, E., 2014. "Il Senato e la Damnatio Memoriae da Caligola a Domiziano". Politica Antica 4, 33-53.

Carradice, I.A. 1983. Coinage and Finances in the Reign of Domitian, AD 81-96. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports.

Cassius Dio, Roman History, Book 67.

Jones, B. 1992. The Emperor Domitian. London and New York: Routledge.

Martial, Epigrammata.

Southern, P. 1997. Domitian: Tragic Tyrant. London and New York: Routledge.

Statius, Silvae.

Suetonius, Life of Domitian.

Tacitus, Agricola.

Waters, K.H. 1963. "The Character of Domitian". Phoenix 18, 49-77.

.png)

Comments